Friday, March 30, 2012

Monday, March 26, 2012

That Wild Music (Just a fragment of a draft)

For the youth of the world is passed and the strength of creation is already exhausted...and the pitcher is near to the cistern and the ship to the port, and the course of the journey to the city and life to its consummation". (2 Bar. 85:10)

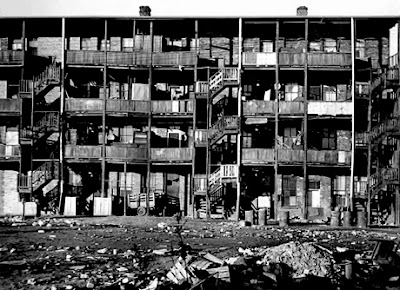

The city was extremely hot that summer -- hotter even than it ever was in Montgomery - - and this caused a distinctive stink to rise up from the already stinking city sewers, engendering a sort of highly-distilled foecalurine perfume that followed you around town, as if the city had its finger held under your nose. Like the French Opera, which becomes a container for the all the varieties of perfumes and powders which those ladies apply in an effort to combat what I’m told are their menstrual odours, causing the various scents, purchased separately and at great expense, to congeal into an indistinguishable brown of oriental flowers and spice (haunted by the ghost of their body’s original scent, radiating from the armpits and the groin); so the city became a sort of vapourbox for its own effluence, wafting up from the treatment plant, the beef farms outside the city, and more lately, from the houses in the Western suburbs, which had been most severely visited by what was then being called the fever - but which was not a fever, really, at all.

***

It was always beef fat and never lard, even if we had any lard available. There is a special enzyme present in the meat of the former, I’m told, which makes it useful. I used to stand out on the ridge, my hands and lower arms covered in tallow, watching them move across the fields outside the city, scattering and reforming like flocks of sparrows. All we could do was to apply pressure as evenly as possible, going out sometimes weekly, sometimes twice a week, making sure no one got too comfortable. And really, I couldn’t help feeling a little guilty sometimes, and some of the boys even went so far as to warn them ahead of time, so that when we swept through, there was hardly anything left.

Always a great big bonfire after though, which could be fun sometimes, and served both as a means of disposing of the trash, and as a sort of primitive communication to anyone who might be watching from deeper in the fields. Always beef fat to the exclusion of lard.

I used to think about Nebuchadnezzar, set outside the Lion’s gates, talking to and eating with cattle, going around naked and, presumably, shitting in the fields, pissing in the fields; letting his hair grow long, letting his beard grow long, letting his nails grow long; wearing no shoes, and letting his feet get filthy and black; picking through bones and guts left by larger animals; scaring away birds and foxes; going not to the feasts, going not to the dances, going not to the opera, or to the recital or the theatre, but sitting in a cave, smearing his neck and face with shit, taking something from every category of filth, covering himself with all hues of brown, so that nothing showed but the golden earring which he passed over when stripping himself of everything else, shining out like a jewel in an Ethiope’s ear; hung in ghastly night, visible by those within the city walls only in hallucinatory, deformed echoes, streaking across the night in his mad runnings across the grass.

And it’s true. I walked around most days in a dirty shirt. But so did almost everyone else. And so everyone was lousy and scratching their shoulders and scalps, and didn’t even bother changing their clothes.

“I’m not exaggerating boys – the whole damn town smells like a boiling pot of the deepest, yellowist piss I ever took.”

“He’s right, it does.”

Going back and forth between both ends of the city, there was an increasingly noticeable contrast in the amounts of foot-traffic. It was almost only exclusively police who passed between neighborhoods, as there was an emerging popular conception that it was dangerous, that the west end was becoming what they called a no-go zone. They were basically right, but I made the trip routinely, locked in a kind of unstable magnetic suspension between the two poles.

Ethel the hard-titted, the scrupulously clean; Jenny the bow-legged, the absolutely filthy.

In fact, that’s almost all I did for several weeks, starting in May. Trudging back and forth, coming and going, sleeping now East in the tower, now West in the attic; now uptown Henry, now downtown Mr. Roebuck – sometimes nights at the one with blood still flowing from the morning at the other - with fingers still pinching and stroking themselves habitually, like the Norse god whose head still bites the dust after falling from the body.

By that time, Ethel was getting less and less eager to put her mouth on any part of me, and went so far as to insist that I dip my nether regions in a bowl of vinegar which she hat set up near the sink for that purpose. You couldn’t argue with the fact that the fumes did seem to cut through the thickness of the air, forming a pocket of sterility that Ethel would breathe in greedily, as if surfacing unexpectedly in some underwater oxygen reservoir.

And when you’re elbow deep in manmuck and womanflesh, any squeamishness about dipping your genitals in vinegar soon vanishes.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)